Optimizing Iterative Learning: A Tale of Two Cycles

by Michael Peterson

July 1, 2021

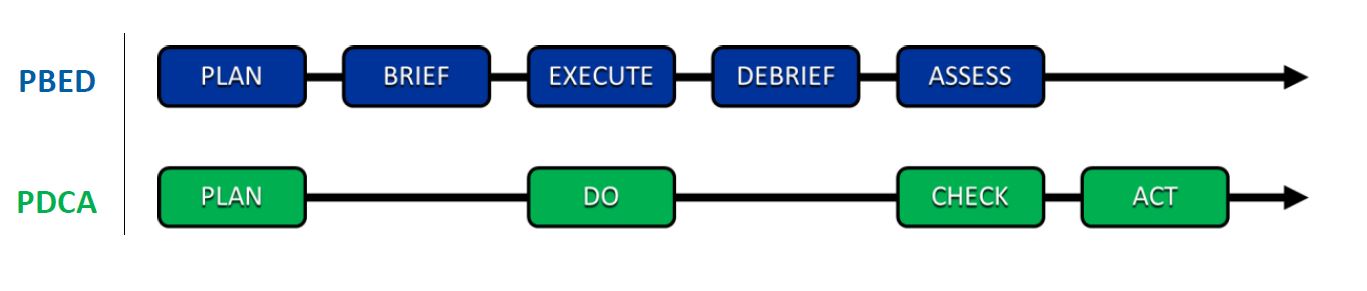

For decades, U.S. military aviation and special forces have leveraged the iterative Plan-Brief-Execute-Debrief (PBED) Cycle (which also includes an assess step) as a standardized means of generating continuous improvement to enhance mission execution and success. This process is deeply engrained in their culture from initial individual training, to real-world elite team operations, to strategic global incident response. Due to its success, it has been adopted by other elements within all military branches, civilian first responders, and many corporate organizations as a means to optimize safety and performance.

For decades, U.S. military aviation and special forces have leveraged the iterative Plan-Brief-Execute-Debrief (PBED) Cycle (which also includes an assess step) as a standardized means of generating continuous improvement to enhance mission execution and success. This process is deeply engrained in their culture from initial individual training, to real-world elite team operations, to strategic global incident response. Due to its success, it has been adopted by other elements within all military branches, civilian first responders, and many corporate organizations as a means to optimize safety and performance.  But there is another, more widely known iterative improvement cycle being used by many organizations – the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) Cycle.

But there is another, more widely known iterative improvement cycle being used by many organizations – the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) Cycle.

On first look, the cycles appear similar in form and function – both are intended to be used iteratively to continuously improve on previous performance through organizational and operational learning and/or to solve operational issues. However, their seemingly small differences are significant in their ability to adapt to dynamic events and human factors, create adaptive capacity to react to unexpected events, improve leadership and teamwork in addition to processes and products, and positively affect future iterations of a task.

By combining the best aspects of each cycle,

iterative learning can be improved to ensure any organization

optimizes its organizational and operational performance.

PBED is intended to be integrated into all tasks, both routine and non-routine, whereas PDCA is often used by organizations only as part of selected improvement evolutions (e.g. as a Kaizen or other formal process). In this respect, PBED-style implementation has the potential to involve more people and perspectives in continuous improvement efforts, especially the frontline workers closest to challenges and opportunities associated with work. Increased iterations and greater participation serves to better reinforce the cultural aspects of continuous improvement throughout the entire organization.

The PLAN steps in each cycle closely resemble each other with PBED usually starting with the current best-known practice and explicitly including formal risk management in the plan and PDCA planning tending to be more hypothetical in nature. It is important to note that either cycle can be applied to both routine and non-routine work of varying complexity. Less planning time can be allotted to known situations and environments while more time should be spent on complex, dynamic, or novel tasks to include dedicated contingency planning.

PBED incorporates a critical BRIEF step that is absent in the PDCA cycle.

Briefing is critical to creating adaptive capacity that

leads to operational reliability and resilience.

Conducting a pre-job brief offers the leaders and team executing the task the opportunity to account for issues that were unknown at the time of planning or undiscovered by planners who are often different than the operators performing the task. Briefing aligns the team members to common goals and allows the team to account for dynamic environments, conflicting operations, and human factors such as fatigue, skill/experience, proficiency, impairment, and other issues. Plans can be adjusted to increase likelihood of success and increases collaboration and teamwork by defining and acknowledging roles and responsibilities which is a critical enabler of mutual support.

The EXECUTE and DO phases in each cycle both focus on reliable task completion, i.e. getting the job done right the first time. PBED emphasizes intelligent teams and use of cognitive and collaborative non-technical skills to meet the planners’ intent through capacity and flexibility in the face of changing conditions and unexpected events. This requires an understanding of intent created during planning and communicated during the brief and adaptive capacity – the means and will to adjust to changing conditions in measurable terms to achieve success.

PDCA usually emphasizes testing new approaches by increasing the scale and scope of testing with each iteration to control variables and associated risk while capturing data to inform performance analysis.

Like with the PLAN step, both cycles can be adapted to suit routine and non-routine work of varying complexity. The more new, complex, or risky the task, the more mutual performance monitoring and support or controls are introduced into task execution.

The dedicated DEBRIEF step is unique to the PBED cycle.

Debriefing offers an opportunity for leadership,

humble self-reflection, ownership of performance, and

the ability to enhance team relationships and trust.

Realizing that results could be driven by deficiencies in either planning, briefing, or individual or team performance, the debrief examines each element for potential improvement by bringing individual’s unique perspective to bear. When leaders offer a humble self-critique, it creates psychological safety for others to offer critiques of themselves and teammates that promote future self-imposed discipline and commitment to the team and the larger organization.

Both the PBED ASSESS and PDCA CHECK steps seek to evaluate plans and performance with the intent to learn from the previous steps in the cycle. Discussions should avoid assigning blame for failures to individuals but seek to better understand how things can be improved by focusing on what and why questions. Learning is scalable and can range from enhancing individual knowledge, skill, and proficiency to improvements in team interaction and leadership techniques to procedural or policy changes that have the potential to benefit the entire organization or an industry.

The explicit ACT phase in the PDCA cycle ensures that learning affects future iterations of a task. The lack of this explicit step in the PBED cycle often restricts learning to the individual or small team level and too often results in “lessons relearned” instead of continuous improvement. This step requires connecting workers performing the task with other personnel that have influence over the system and follow through to update procedures and policies and communicate changes and the reasons behind them to all affected employees.

When conducted correctly, each cycle offers potential continuous improvement and serves to better inform the organization about the intent of work as imagined and the necessary variance in work as done.

Recommendations:

• Use the best aspects of the PBED and PDCA cycles to optimize teams, learning, and

continuous improvement.

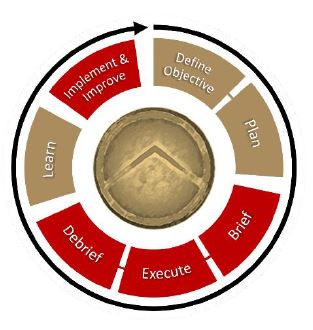

o SPARTAN Training & Performance has created a hybrid cycle that integrates the best aspects of

the PBED and PDCA cycles

• Employ cyclical iterative learning for all tasks to leverage the power of

crowdsourcing of innovation.

• Always start planning by using SMART (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic,

Time-bound) criteria for your objective(s).

• Scale planning and execution to meet the characteristics

of the assigned task – routine/non-routine, complexity, dynamic environments, risk, etc.

• Leverage the power of a pre-job brief to align the team to common goals; account for

differences in planning assumptions and real-world conditions in environment, equipment, and team;

and better enable teamwork and mutual support during task execution.

• Always debrief performance to promote aspects of leadership, ownership, and team optimization in addition to assessing plans, procedures, and policies.

• Assess and capture learning created during the debrief and assess/check steps and evaluate it potential impact to positively affect others outside of the team performing the work

References:

1 – United States Department of The Navy, Navy Planning, Navy Warfare Publication NWP 5-01, December 2013, p. 1-10.

2 – The W. Edwards Deming Institute, PDSA Cycle, https://deming.org/explore/pdsa/, accessed July 7, 2021.

About the Author:

Michael “Tung” Peterson is a Navy Fighter Weapons School (i.e., TOPGUN) graduate and former Strike Fighter Weapon and Tactics School Instructor in the F-14 Tomcat and F/A-18F Super Hornet. He is a former Assistant Professor of Military & Strategic Studies at the United States Air Force Academy who holds a M.A. in Security Studies from the Naval Postgraduate School and a B.S. from the U.S. Naval Academy. He is a founding member of SPARTAN Training & Performance, an avid outdoorsman, and vocal advocate for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. He resides in Colorado with his wife and three daughters.

© 2021 SPARTAN Training & Performance