Human & Organizational Performance -

The Red Pill of Reliability

by Tim Reynolds and Michael Peterson

March 24, 2021

The company man just finished his pre-job brief and it was time to go to work. I approached him with an offer he couldn’t refuse. “I can guarantee you’ll meet your objective tonight.” I calmly stated.

Bob, the oil company’s representative on the rig, stared at me suspiciously for a few moments and then said, “Ok, I’ll bite. What do you mean?”

“Well…you just briefed your crew that the sole objective tonight while running casing was to be safe, right?”

“Yes,” he replied.

“Ok, so why don’t we bring your casing crew down to the safety trailer and I’ll make coffee and heat up some food? We can take the night off and then hand off this task to the day crew tomorrow morning.”

“What? Are you crazy? We can’t do that! We’ve got to run thousands of feet of casing downhole. We can’t take the night off.”

“But,” I countered, “you just briefed 15 or so folks that the ONLY objective tonight was to be safe, right?”

“Yes…but we have to get the job done.”

“Ok,” I said. “Then what IS your objective?”

“Ok, Ok Hoolie, I get your point. My objective is to successfully run thousands of feet of casing downhole AND do it SAFELY.”

“Great!” I exclaimed, “but I do have one concern.”

“What’s that?” he asked.

“We spent a lot of time discussing what the team was NOT going to do tonight – no slips, trips, or falls; no hands in pinch points; no walking between the stump and the tongs etc… Why didn’t we spend any time discussing what we were going to do?”

This story is typical of many of my interactions with industries where error could lead to a catastrophic consequence. A week or so later, I was watching the movie, The Matrix, with my teenage son, and I was struck by what Morpheus said to Neo during the Red Pill vs. Blue Pill conversation. “You don’t know what it is, but it’s there, like a splinter in your mind, driving you mad. It is this feeling that has brought you to me.”

“Ironically, more often than not, the goal of any task was to NOT do something.”

The splinter in my mind was the obvious fact that, in most professions, safety isn’t really first. In fact, many organizations and industries spend a tremendous amount of time and energy focusing on what shouldn’t happen to the exclusion of the actual task at hand. They neglect reliability – what should happen, what each individual’s role is in making it happen, and the performance expectations of the team. Ironically, more often than not, the goal of any task was to not do something. Organizations that embrace a “Goal Zero” mindset are a prime example. How does one aspire “not to do something?” In other words, avoiding actions construed as negative were seen as taking a positive action.

Oddly, I first experienced the same “splinter in my mind” decades earlier as a junior US Navy pilot during my first deployment. On one particular night, I was scheduled to launch on a training mission. An aircraft carrier catapult is essentially a massive slingshot that sends a fully loaded aircraft and crew from a standstill to over 150 knots flying speed in just over two seconds. The mission that night was to join up with a dozen aircraft, refuel from an airborne tanker, and execute a simulated strike followed by a successful arrested landing on the aircraft carrier. It was the last event of the night and there was no moon or ambient light from the coast hundreds of miles away and the stars were blanked by high-level cloud cover. All of which means it was really dark; except for the flashes of lightning as severe weather rolled in. To add to my stress, the sea was getting increasingly restless, and the flight deck swayed rhythmically with a combination of the ship’s roll, pitch, and yaw. Most concerning, however, was the ship’s heave – when the entire carrier rises and drops in the long troughs between wave tops causing the flight deck to unexpectedly rise up to meet landing aircraft putting them in danger of a ramp strike. To say I was slightly nervous as a newer pilot would be an understatement.

Oddly, I first experienced the same “splinter in my mind” decades earlier as a junior US Navy pilot during my first deployment. On one particular night, I was scheduled to launch on a training mission. An aircraft carrier catapult is essentially a massive slingshot that sends a fully loaded aircraft and crew from a standstill to over 150 knots flying speed in just over two seconds. The mission that night was to join up with a dozen aircraft, refuel from an airborne tanker, and execute a simulated strike followed by a successful arrested landing on the aircraft carrier. It was the last event of the night and there was no moon or ambient light from the coast hundreds of miles away and the stars were blanked by high-level cloud cover. All of which means it was really dark; except for the flashes of lightning as severe weather rolled in. To add to my stress, the sea was getting increasingly restless, and the flight deck swayed rhythmically with a combination of the ship’s roll, pitch, and yaw. Most concerning, however, was the ship’s heave – when the entire carrier rises and drops in the long troughs between wave tops causing the flight deck to unexpectedly rise up to meet landing aircraft putting them in danger of a ramp strike. To say I was slightly nervous as a newer pilot would be an understatement.

As I was walked through the passageway on the ship to man up my aircraft, I passed a large poster that read “Safety First” and featured platitudes about how important safety was to the Navy – I don’t recall the exact slogans. I stopped, stared at the poster, and actually said “Bulls**t!” aloud. If the Navy really believed in safety first, they’d send us back to bed instead of launching aircraft from a moving ship into severe weather and a high sea state at night to perform some routine training mission. While I knew safety was important, I wasn’t fooled by this sloganeering. Building our capacity to perform the mission and successfully executing our mission in the real world when called to do so was why naval aviation exists – an aircraft carrier isn’t meant to just carry aircraft.

This understanding of the relationship of safety and mission solidified during my first years as a naval aviator. Later, my perspective evolved to better understand safety as an essential derivative of mission success – something that was only possible in complex, dynamic, high-threat environments through the disciplined use of leadership, teamwork, flexibility, and real-time risk management. While I didn’t recognize many of these principles, supporting tools, and leadership techniques as core elements of Human & Organizational Performance (HOP), I do today. We didn’t explicitly call it “adaptive capacity” at the time, we just knew it was essential to accomplish our mission safely and effectively in the face of the ever-present fog and friction of the battlefield.

“While I didn’t recognize many of these principles, supporting tools, and leadership techniques as core elements of Human & Organizational Performance (HOP), I do today.”

HOP is not so much a program as it is a distinct way of thinking. If adopted and fully incorporated into an organization’s culture, I believe HOP has the power to help organization better balance safety and operational reliability. Among its tenets, HOP acknowledges human fallibility – people will make mistakes regardless of one’s training, knowledge, or skill – but it also recognizes that people are the most flexible, adaptable, and creative component of modern systems.

Additionally, HOP moves away from a focus on administrative and bureaucratic compliance to a focus on operations and why things usually go right.1 Therefore, it moves from seeing workers as problems to be solved, to seeing workers as problem solvers.2

Prior to a big fight, Mike Tyson was once asked how he would handle an opponent that planned to dance around the ring and use a lot of lateral movement. Tyson responded by saying, “Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.” For those who fly off aircraft carriers or who work in other high consequence industries, what do they do when they get punched in the mouth? Do they have the capacity and resilience to deal with the unexpected events that eventually happen? They measure success by their capacity to adjust to dynamic and unexpected events while continuing their mission and to degrade gracefully when confronted by events they cannot overcome.

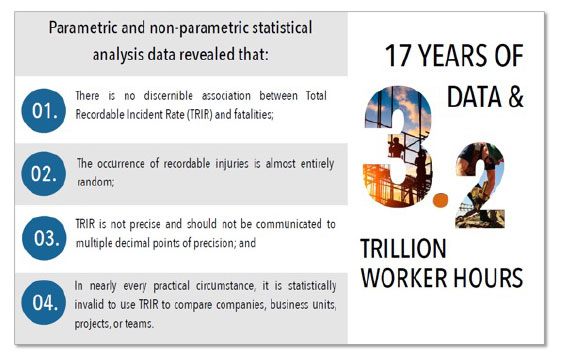

So, why do companies spend so much time and effort measuring success by the absence of bad things happening? Total Recordable Incident Rate (TRIR) has been used as the primary measure of safety performance for nearly 50 years – since the definition of a “recordable incident” was institutionalized by the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970. A November 2020 study challenges the orthodoxy of TRIR as a statistically valid safety metric.3 The key findings are disruptive to the prevalent safety measurement paradigm:4

None of this is to suggest that companies should not track recordable incidents. Moreover, it’s hard to imagine insurance actuaries moving off this metric to assess major industries. However, the use of TRIR as a predictive tool should be reconsidered. Equally, if an organization is using TRIR for performance evaluations, they are likely rewarding nothing more than random variation in safety and neglecting other aspects of performance. Worse yet, they may foster an environment that discourages the robust reporting that fuels identification and remediation of latent systemic errors in order to maintain the appearance of perfection or to meet goal zero targets. Their well-intended safety program is actually making them less safe!

Jerry Muller in The Tyranny of Metrics cautions us to be wary of simple metrics. “The more numeric, visible, and reward-tied a metric is, the more likely it is to be gamed and turn toxic to its original purpose.” 5 TRIR offers us seductively unambiguous information that, unfortunately, has proven to be a poor indicator of future trends and is disconnected from an organization’s capacity to deal with adversity and unexpected events.

Interestingly, studies over the last 20 years have shown a strong relationship between reporting and incidents, however, the relationship is negatively correlated. In short, the more numerous reporting of minor incidents, the fewer major incidents and fatalities a company or industry experiences. 6,7,8 Furthermore, you’re more likely to have serious incidents and/or fatalities with a “goal zero” safety policy. Admittedly, many companies implicitly recognize this fact, however, they don’t seem able to move beyond the old way of thinking.

Like the opening conversation with Bob the company man, I’ve observed an overemphasis on avoidance of negative outcomes on numerous occasions. Take a typical pre-job safety briefing that occurs in multiple industries: drilling, construction, shipyards, etc.. More often than not, the team performing the task has a Job Safety Analysis (JSA) which identifies the hazards and steps to mitigate the known risk. Depending on the task, there may also be a variety of Permits to Work (PTW) or other paperwork that must be completed prior to execution. In the most egregious cases, compliance with and completion of administrative paperwork alone takes more time to complete than the actual task. When the team gets to discussing the task, it is almost entirely focused on what they will not do instead of the specific objective to be accomplished and how the work should be performed.

Moreover, when asked about performance goals or possible efficiencies, there is often noticeable resistance. During one pre-job meeting, I asked the workers how long a particular task would take them. Later, their supervisor told me not to ask that question because he didn’t want his folks to feel any undue pressure to rush the job. In short, safety and performance were viewed as competing interests, a zero-sum game. One had to be sacrificed in order for the other to thrive.

While all of this administrative paperwork was well intended, it is unintentionally providing a patina of safety while hiding all sorts of latent dysfunction and inefficiencies. This approach may have helped in the past, but today it is inhibiting the ability to remain competitive in increasing complex and dynamic environments. More rules, more paperwork, and more administrative compliance do not lead to a safer work environment. Legacy views of safety implemented using a top-down, comply-and-control philosophy are not making organizations safer or more competitive.

While all of this administrative paperwork was well intended, it is unintentionally providing a patina of safety while hiding all sorts of latent dysfunction and inefficiencies. This approach may have helped in the past, but today it is inhibiting the ability to remain competitive in increasing complex and dynamic environments. More rules, more paperwork, and more administrative compliance do not lead to a safer work environment. Legacy views of safety implemented using a top-down, comply-and-control philosophy are not making organizations safer or more competitive.

This is where I come back to HOP and its focus on continuous learning and adaptive capacity to produce reliable results. “Reliability” encompasses predictability, repeatability, efficiency, and quality as well as safety. HOP allows practitioners to eliminate the errant focus on avoiding negative outcomes and focus on reliable operations – why a job usually goes right and how to build additional capacity in those areas. HOP recognizes that operational execution is dynamic and that “making systems work… is the great task of our generation as a whole. In every field knowledge has exploded, but it has brought complexity, it has brought specialization. …as individualistic as we want to be, complexity requires group success.” 9 HOP offers the agility to deal with specialization, complexity, and the unknown by connecting an organization to collaborate through teamwork to achieve common goals.

“HOP allows practitioners to eliminate the errant focus on avoiding negative outcomes and focus on reliability – why a job usually goes right, and how to build additional capacity in those areas.”

I get it. HOP principles may initially seem abstract. How does one go about translating these deeply held beliefs into something tangible that can be implemented and comfortably measured? Implementing a HOP culture is a journey. It won’t happen in a short timeframe. It starts with a philosophical shift in thinking about how work is done in the real world. While some managers and executives may cringe at the academic nature of HOP, many of your employees already get it. One of the principles of high reliability organizations is “deference to expertise.” 10 Many of your experts are on the frontline closest to the challenges and opportunities of how work is done and are masters of adaptive behavior. They constantly adjust to the changing environments, equipment issues, and team dynamics. HOP engages and empowers those closest to the work to define what they need to solve problems and realize opportunities to benefit their organization. HOP is an approach built from the bottom-up based on psychological safety, collaborative learning, respect for diverse perspectives, and mutual support.

Following my evening conversation with Bob the company man about avoiding negative outcomes, we reconvened in the doghouse, the control room adjacent to the rig floor, to discuss more thoroughly what his team would be doing that night. We discussed SMART objectives, task assignments, roles and responsibilities, contingencies, and communications. We set expectations for team performance and mutual support. Following successful execution, we then debriefed the event; what worked, what didn’t, and how we might execute this task differently the next time. That was the start of creating a learning environment and developing the adaptive capacity that leads to reliability.

In the Matrix, choosing the red pill symbolized recognizing an unpleasant truth while the blue pill was the choice to remain blissfully ignorant of reality. More and more companies today are willing to recognize that, maybe, safety through avoidance of negative events isn’t the best policy. They are starting to explore a new HOP-based approach that increases safety through a focus on operations and building positive capacity. One year after taking the red pill of reliability, Bob and his company continue their operational focus resulting in both improved safety and performance and they remain on their HOP journey today.

In the Matrix, choosing the red pill symbolized recognizing an unpleasant truth while the blue pill was the choice to remain blissfully ignorant of reality. More and more companies today are willing to recognize that, maybe, safety through avoidance of negative events isn’t the best policy. They are starting to explore a new HOP-based approach that increases safety through a focus on operations and building positive capacity. One year after taking the red pill of reliability, Bob and his company continue their operational focus resulting in both improved safety and performance and they remain on their HOP journey today.

References:

1 – Hollnagel, Erik, Safety- II in Practice: Developing the Resilience Potentials, Routledge, New York, NY, 2018.

2 – Dekker, Sydney, “Safety Differently |The Movie”, SafetyDifferently.com, 2017. https://safetydifferently.com/safety-differently-the-movie/

3 – Hallowell, Quashne, Salas, Jones, MacLean, & Quinn, The Statistical Invalidity of TRIR as a Measure of Safety Performance, Construction Safety Research Alliance, Boulder, CO, 2020.

4 – Ibid.

5 – Muller, J., The Tyranny of Metrics, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 2018.

6 – Saloniemi, Antti, and Hanna E. Oksanen, “Accidents and Fatal Accidents — Some Paradoxes”, Safety Science 29, 1998.

7 – Flight Safety Foundation, “Passenger-Mortality Risk Estimates Provide Perspectives About Airline Safety”, Flight Safety Digest, Apr 2000.

8 – University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Conditions Reporting System Helps Foster Culture of Safety, Oct 2012.

9 – Gawande, Atul, TED2012: How Do We Heal Medicine?, TED Talks, March 2012, https://www.ted.com/talks/atul_gawande_how_do_we_heal_medicine

10 – Weick, Karl E., and Sutcliffe, Kathleen M., Managing the Unexpected: Resilient Performance in an Age of Uncertainty, 3rd ed., John Wiley & Sons, 2015.

11 – Initial SMART objective criteria developed by Doran, G. T., “There’s a S.M.A.R.T. way to write management’s goals and objectives”. Management Review, 1981.

About the Authors:

Tim “Hoolie” Reynolds is a former EMT and 25-year US Navy veteran where he commanded a an electronic attack squadron and was a Command Center Director at NORAD/US Northern Command, charged with Defense Support of Civil Authorities and the military defense of the US homeland. He is a founding member of SPARTAN Training & Performance, a HOP-focused consultancy. He is a certified Aviation Safety Officer who holds an MA in Strategic Studies from the Naval War College and a BA from the University of California, Berkeley. Tim and his wife live in Colorado with two children in college and two more at home. They enjoy hiking, skiing, travelling, and spending time with family and friends.

Michael “Tung” Peterson is a Navy Fighter Weapons School (i.e., TOPGUN) graduate and former Strike Fighter Weapon and Tactics School Instructor in the F-14 Tomcat and F/A-18F Super Hornet. He is a former Assistant Professor of Military & Strategic Studies at the United States Air Force Academy who holds an MA in Security Studies from the Naval Postgraduate School and a BS from the US Naval Academy. He is a founding member of SPARTAN Training & Performance, an avid outdoorsman, and vocal advocate for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. He resides in Colorado with his wife and three daughters